During World War I, Australian families received postcards and letters from their sons fighting abroad. These were brief, polite, and matter-of-fact messages. One came from Maurice Delpratt; a soldier, a Queenslander, and an ANZAC. In July, 1915 in Constantinople, Delpratt writes: “And here I am, a prisoner of war, having failed in my mission and no longer able to serve my country, but in good health and looking forward to the day when the war ends and I can go home. With the Australians, it is considered a disgrace to be captured.” Delpratt continues by thanking those who sent letters to him. His message ends with instructions for his family to write back to Delpratt. Yet these technical details about communication in wartime are not the most fascinating part of the letter. Nor are the historical tidbits about Constantinople, or even ANZACs being taken as prisoners of war.

Rather, the most memorable aspect is Delpratt’s regret, and guilt, in being captured and thus, failing in his mission. He takes an apologetic tone: “It was bad soldiering on my part to get within the enemy’s advanced lines, but I know you will understand it is not lack of courage (that) makes a man do that.” Delpratt’s bravery, and urgency to fight for Australia, is evident. Yet the emotional potency of the letter comes from his remorse. It’s a vulnerable moment, and the reader can better understand the harsh nature of war through Maurice Delpratt’s experiences. He would survive World War I and have a family, before dying in 1957.

Postcards may seem antiquated in our age of social media, e-mail, and broadcast television. But during World War I, and much of their history, postcards represented one of the few communication avenues between families and soldiers. They aren’t the only source used by historians to understand soldiers: official records, photographs, private diaries, and death records illuminate the experiences of soldiers in World War I. Afterwards, many soldiers would depict their harrowing ordeals through art, literature, political manifestos, and journalism.

Why Culture Matters To War Studies: A Video

One such example comes from the Central Powers; Otto Dix, a German printmaker and painter, who transformed his trauma into Stormtroopers Advancing Under Gas (1924), part of ‘Der Krieg,’ or, ‘The War.’ These drypoint etchings suggest the hellish landscapes created by Francisco Goya, Hieronymus Bosch, and Dante Alighieri. Dix depicts numerous events of WWI, from men being buried alive, to the Battle of the Somme in 1916, as well as corpses strung in barbed wire. There are skulls, destroyed houses, gas masks, bodies in trenches, and the ruins of Langemarck. Here, Otto Dix confronts his audience with the ghoulish reality of war. This did not win much love from Weimar and National Socialist viewers in the 1920s and 1930s. Yet Otto Dix was no exception. The caustic and tragic saga – All Quiet on the Western Front – took form from the observations, and tragedies, of German veteran Erich Maria Remarque, and that of his fellow countrymen. To Goebbels, Remarque was ‘unpatriotic’ who tarnished the German military and nation, and thus, the novel was banned in the Third Reich. Yet the books’ epigraph tells another perspective. Remarque writes: “This book is to be neither an accusation nor a confession, and least of all an adventure, for death is not an adventure to those who stand face to face with it. It will try simply to tell of a generation of men who, even though they may have escaped shells, were destroyed by the war.”

Otto Dix and Erich Maria Remarque are just two examples of art giving form to the experiences of World War I. Others, whether they fought for the Central Powers or the Triple Entente, have shaped common perceptions about World War I across the West. A well-known example is J.R.R Tolkien. While Middle-Earth from Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit is akin to myth, Tolkien fought for the British and became acquainted with trench warfare, including the Battle of the Somme. The extent to which World War I influenced Tolkien is debatable. Yet certain moments from Middle-Earth, such as the Dead Marshes in The Two Towers, are suggestive of a soldier’s experience (and perhaps, fate) in WWI.

War poetry is also revealing. Rupert Brooke’s The Soldier mourns not only the English dead, but also the state of his country as well as the better days now gone, with idealistic and loving language. Alongside Tolkien, there is a fixation with England prior to total warfare and modernity. His poetry references “her (England’s) flowers” and “a body of England’s, breathing English air, washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.” Romanticism reigned within Brooke. The fixation with nature implies a purity which cannot withstand the machines of war. Brooke died in Skyros, Greece – the result of an infection from a mosquito bite in 1915. He was not the only English poet to die during wartime.

Wilfred Owen offered a grim image with Dulce et Decorum Est. Here, the Salopian soldier depicts death, “as under a green sea, I saw him drowning. In all my dreams, before my helpless sight, he plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.” Owen continues to describe the foulness entrenched onto his fellow soldiers and finishes with a sour warning about chasing glory. A week before the Armistice in November 1918, Wilfred Owen was killed in action in Northern France. He is remembered today as one of the finest English poets of World War I. Outside of poetry and the visual arts, it is quite common for English, French, and German churches to have the names of dead parishioners on a plaque. I observed this while in Northern France; the grand and gorgeous Churches, such as the medieval Saint-Germain des Pres in Paris, commemorate the soldiers who sacrificed their lives for their country. The esteemed Westminster Abbey in London has the grave of the unknown warrior, as do other Anglosphere nations. These monuments do not necessarily convey the widespread carnage inflicted onto Europe during WWI. The names of the dead, as well as their year of birth, are engraved onto the wall as if it were a gravestone. I look at these memorials and am again reminded of the many men who died in World War I. They had families, parishes, communities, hobbies, dreams, and friends. It is our responsibility – as Westerners – to commemorate these men. The Jesuit high school in Lane Cove does this, too.

In the courtyard of St. Ignatius College, Riverview’s chapel, there are several memorial boards to the students who died in WWI. On ANZAC and Remembrance Day, tiny red poppies bloom out next to their names as if they came from soil. There is also a memorial to Australians who fought in Crete during WWII. I visit St. Ignatius College on ANZAC Day, 2024. With the school having no classes or events due to the public holiday, I walked around the fields, the courtyards, and the roads, where a decade prior, my brothers and my cousins roamed as Riverview boys. They played rugby, joked about one another, stressed over exams, and wondered what career suited them best. War belonged in textbooks, at ANZAC services, and in debates about the Middle East and North Africa, where the Arab Spring loomed in Eurasia yet far from home. Australians today are unfamiliar with war. It exists as a political argument, a protest slogan, or as a historical topic. While alone in the St. Ignatius courtyard, I take a minute to appreciate the memorials to the dead. I do not desire a country where the sacrifices of young men are taken for granted or forgotten, as if they were never there.

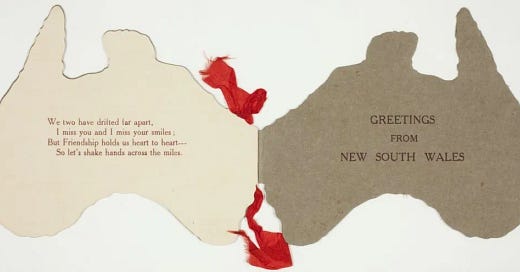

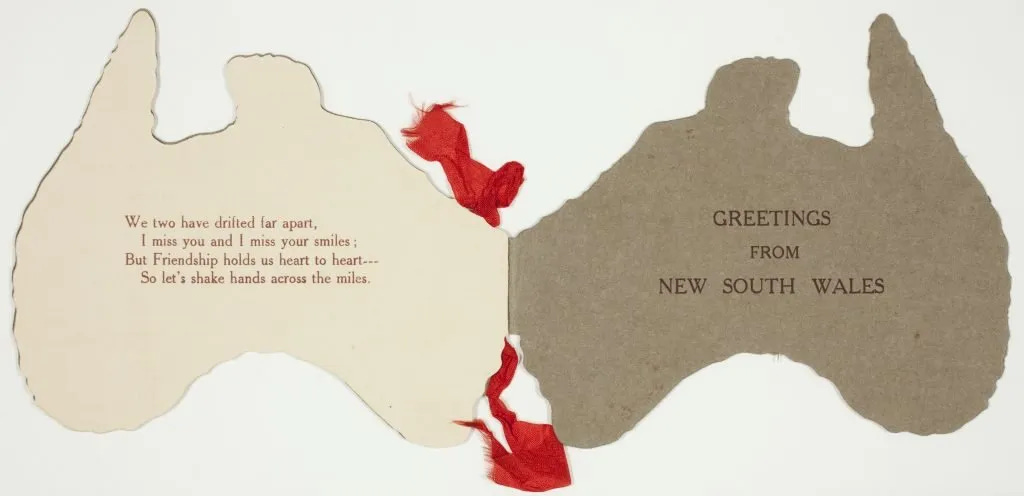

Postcards, by comparison, are not works of art or memorials to the dead. They are brief, often private, and shared during wartime. Visually, the front illustration can seem nationalistic and at worst, an example of propaganda. You’ll find lyrics to national anthems, Australian flora and fauna, as well as seasonal greetings to mark certain occasions, such as Christmas. The Mitchell Library from the State Library of New South Wales has preserved and digitised over a hundred examples of cards and postcards from World War I. One such example is a postcard with kookaburras on the cover, illustrated in spectacular colour, alongside the words, ‘a token from Australia.’ Song lyrics are also provided. “This fair land of sunshine far over the foam, but this picture brings it near. It is only a bird lilting an evening song, I can hear it so plain. Though long months have passed my love’s just as strong, to see my dear old home again.” Even when postcards are cheerful and colourful, melancholy is conveyed among the birds, the gumtrees, and the wattle. The author ‘yearns for Australia’ where kangaroos roam and farmers are content after a long, tiring day with cattle. He is, as an ANZAC soldier in Southeastern Europe, so far from his Australian home. These postcards provoke profound sadness. Many of these men did not return to Australia and are now buried in Anatolia, their bones nestled in dirt and stone. Postcards tell us about these men, their families and their lives, as well as their Australian identity.

Beyond being a fantastic primary source for students studying modern history, they also illuminate aspects of total warfare not present in cartography, newspaper clippings, hospital records, and briefings made from military staff. The private nature of postcards also ensures they are not cultural sources, either. Whereas a propaganda poster is plastered around in towns and cities for many to see, postcards offer greater intimacy due to its limited audience, which is typically the soldier’s family. Behind every postcard or greeting card is a young man with ambitions, family, and a life prior to warfare. It’s the duty of historians to understand and to humanise these men. Yet this responsibility is not just for historians with PhDs and publications in research journals. Australians living today would greatly benefit from learning about the ANZACs, visiting the many war memorials, reading wartime literature, or seeing the postcards online. We owe it to those who fought, and died, for Australia.

I return to the Mitchell Library. The postcards, Christmas cards, and greetings indicate cheer, and a soldier’s yearning for the comfort found in Australiana. Maurice Delpratt’s letters lurk in my mind like a memory, nearly lost to time. Over 60,000 Australian soldiers died in World War I, and those who survived faced illness, trauma and injury for the remainder of their lives. These postcards and letters allow Australians today, for a brief minute, to understand and appreciate the joys only our homeland can bring.